What Is Microdosing? An Evidence-Based Overview of Its Effects and Controversies

Abstract

Microdosing—the practice of taking small, sub-hallucinogenic doses of psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, or Amanita muscaria—has gained widespread popularity. While users report mood enhancement, cognitive benefits, and improved mental well-being, scientific support remains limited. This article reviews the latest evidence (2020–2025) on microdosing protocols, pharmacology, user motivations, neurobiological mechanisms, and associated risks. It incorporates data from peer-reviewed trials, sociological research, toxicological reports, and harm-reduction strategies. Scientific findings are mixed. Some studies suggest that microdosing may influence mood, neuroplasticity, and cognitive performance, but placebo effects account for many reported benefits. Emerging risks—such as overstimulation, heavy metal accumulation, and unregulated product use—demand careful attention.

While micro dosing remains a popular self-experimentation practice, it is not yet supported by robust clinical evidence. Tools like the Psylocybin QTest enable the measurement of potency before consumption, but legal and physiological uncertainties persist. Future research must clarify its efficacy, long-term safety, and ethical implications.

Author: Dr. Marina Garcia Moreno

March 27, 2025

6 min read

Key Points about Microdosing

- Microdosing involves taking approximately 5–10% of a psychedelic dose to improve mood, creativity, or focus.

- LSD, psilocybin, MDMA, and Amanita muscaria are the most commonly used substances.

- Current clinical studies show modest or placebo-level effects, especially for mood and attention.

- Protocols such as Fadiman’s and Stamets’ are based on anecdotal evidence, not clinical validation.

- Microdosing may involve physiological risks, including cardiovascular changes, overstimulation, and toxicity.

- LSD, MDMA and Psilocybin QTests are a harm-reduction tool that allows users to measure compound potency and ensure dose precision.

Introduction

Microdosing psychedelics has emerged as a global trend that blends self-experimentation, mental health strategies, and cognitive enhancement. Once confined to fringe communities and biohacker forums, it now attracts professionals, creatives, and patients alike. In contrast to full-dose psychedelic experiences, microdosing involves taking small, regular doses—low enough to avoid perceptual distortions, yet intended to produce psychological or physiological benefits.

Proponents describe it as a way to enhance creativity, stabilize mood, and foster emotional clarity. Popular platforms, podcasts, and influencers have helped normalize microdosing as a “functional wellness” tool. However, despite its widespread adoption, scientific research has not yet caught up. The question remains: is microdosing an effective therapeutic approach, a cultural placebo, or something in between?

This blog article synthesizes the current state of knowledge around microdosing in 2025—from neurobiological findings to real-world risks, dosing protocols. Its goal is to provide a balanced, non-apologetic review for those curious, cautious, or considering clinical application.

What Is Microdosing and How Is It Practiced?

Microdosing is generally defined as the repeated administration of a sub-threshold dose of a psychedelic substance. The idea is to achieve subtle but cumulative benefits over time—improved focus, emotional resilience, or cognitive agility—without the intense experience of a full psychedelic trip.

Table 1. Microdose ranges, full dose equivalents, and mechanisms of action for commonly reported substances used in microdosing practices. Data compiled and adapted from Modzelewski et al. (2025), Kinderlehrer (2025), Cameron et al. (2021), and information retrieved from the Microdosing Institute and ACS Lab Amanita Guide.

| Substance | Microdose Range | Full Dose Equivalent | Mechanism of Action |

| LSD | 5–20 µg | 100–200 µg | 5-HT2A agonist (serotonergic) |

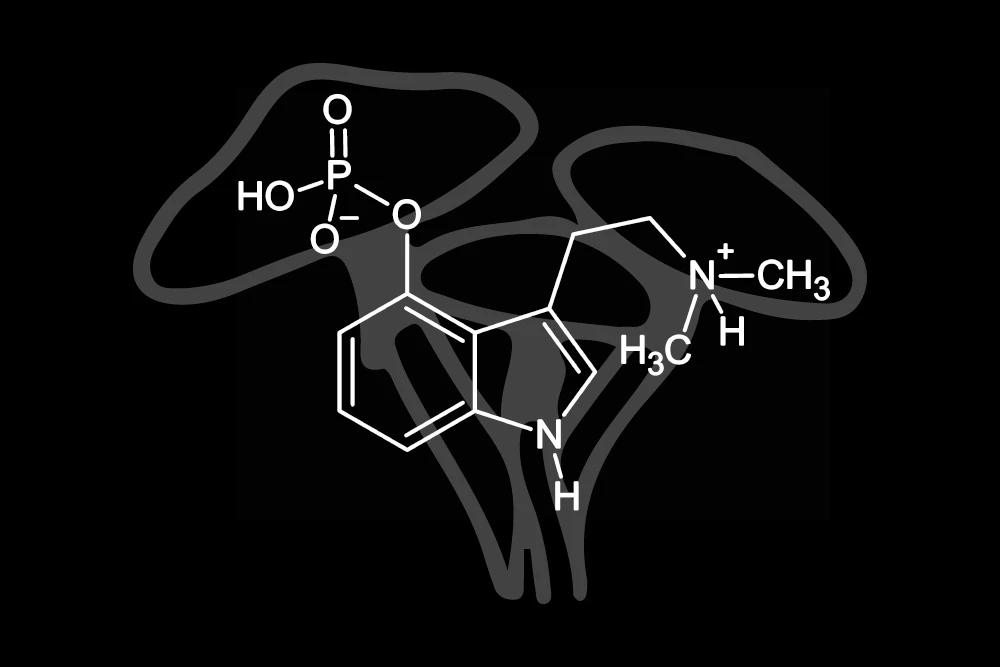

| Psilocybin | 0.1–0.5 g dried / 1–5 mg | 3–5 g dried or ~25 mg synthetic | Serotonin agonist via psilocin |

| MDMA | 1–5 mg | 75–125 mg | Monoamine releaser (5-HT, DA, NE) |

| Amanita muscaria | 50–200 mg dried cap/extract | 1–3 g dried | GABA-A agonist (via muscimol) |

While LSD and psilocybin are serotonergic psychedelics, MDMA is an empathogen with different neurochemical dynamics. Amanita muscaria, on the other hand, is not serotonergic at all—it contains muscimol, a compound that acts on the GABA-A receptor, producing sedation or mild stimulation depending on the dose.

What Does the Science Say?

1. Placebo Effects and Psychological Expectation

Recent randomized controlled trials suggest that expectancy may play a larger role than the substance itself. In several studies, participants who believed they had taken a psychedelic reported positive changes—even if they had received a placebo.

These findings complicate interpretation, particularly in self-reported outcomes such as creativity, well-being, and productivity. However, the placebo effect does not negate the user’s experience—it merely highlights the need for more objective outcome measures.

2. Neurobiological Mechanisms

Some experimental research has investigated whether low-dose psychedelics can influence:

- Neuroinflammation

- Serotonin and dopamine regulation

- BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) expression

- Cognitive flexibility and DMN suppression

A 2025 review by Kinderlehrer notes that psilocybin and its metabolite psilocin may reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, modulate serotonin pathways, and support neuroplasticity—effects that could be relevant even at low doses. However, most of this research has been conducted using full psychedelic doses.

Human Studies Involving Psilocybin Microdosing Without LSD (2022–2023)

While anecdotal claims about psilocybin microdosing are widespread, few controlled studies have rigorously evaluated its effects in human subjects. The following summary presents five peer-reviewed investigations published between 2022 and 2023, focusing exclusively on psilocybin (not LSD). These studies used various methodologies, ranging from case reports to randomized placebo-controlled trials, and examined outcomes such as chronic pain, anxiety, mood, and cognitive changes.

Table 2. Summary of human studies investigating psilocybin microdosing (excluding LSD), showing study types, aims, and key outcomes. Findings vary due to differences in design, dosage, and duration. Adapted from Kinderlehrer (2025), Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 21, 146–147. DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S500337

| First Author, Year | Study Title | Main Objectives | Main Findings / Shortcomings |

| Lyes et al., 2023 | Microdosing psilocybin for chronic pain: a case series | Report of 3 cases managing neuropathic pain using psilocybin microdoses | “Robust pain relief” and reduced use of analgesics |

| Kinderlehrer, 2023 | Microdosed psilocybin in neuropsychiatric Lyme disease | Case report on treatment-resistant depression and anxiety | Dramatic improvement within 48 hours despite patient skepticism |

| Rootman et al., 2022 | Mental health in microdosers vs non-microdosers | Prospective study of 953 microdosers vs 180 controls over 30 days | Small to moderate improvements in mood and mental health among microdosers |

| Cavanna et al., 2022 | Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: placebo-controlled trial | Evaluate short-term effects on well-being, creativity, cognition | No subjective effects; only two high doses (500 mg) over one week; limited timeframe |

| Marschall et al., 2022 | Psilocybin microdosing and emotional processing | 3-week crossover study assessing mood, anxiety, and interoception | No consistent benefits; high dose (700 mg), unblinded second half |

Blinded Study Design in LSD Microdosing: Insights from Cameron et al. (2021)

In a 2024 review, scientists compared the effects of microdosing LSD with a placebo. While some mild positive effects on mood, sleep, and social cognition were observed, these benefits were modest, and the placebo effect played a significant role. Thus, many perceived benefits may stem from the expectation of improvement rather than the substances themselves.

A typical microdosing mushrooms experiment is organized to rigorously evaluate the effects of psychedelic substances at reduced doses. Here is an example of how such a study can be structured (Cameron et al., 2021): participants are separated into three groups—one receiving the microdose, another receiving a placebo, and the last group split between both. This results in three experimental groups of approximately the same number of participants following each regimen, without the participants themselves knowing what they were taking. This approach allows for a blinded study design where participants fill out questionnaires afterward.

Figure on the left: Figure adapted from Cameron et al. (2021).

Cameron, L. P. (2021). Asking questions of psychedelic microdosing. eLife, 10, e66920. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.66920

Comparison Table of Microdosing Protocols

Although microdosing remains unregulated and largely experimental, several informal protocols have emerged in popular and clinical contexts. These regimens—such as those proposed by James Fadiman or Paul Stamets—differ in dose, frequency, intended outcomes, and perceived risks. The table below summarizes key characteristics of the most referenced microdosing practices across substances like LSD, psilocybin, MDMA, and Amanita muscaria.

Table 3. Summary of informal and experimental microdosing protocols across various substances. Differences in dosage, stacking components, and risk profiles reflect the lack of clinical standardization in this field.

| Protocol | Typical Dose | Frequency | Reported Benefits | Known Risks | Scientific Support |

| Fadiman | 5–10 µg LSD or 0.1–0.3 g psilocybin | 1 day on, 2 off | Focus, energy, mood | Insomnia, anxiety, tolerance | Low (anecdotal only) |

| Stamets Stack | Psilocybin + Lion’s Mane + B3 | 5 on, 2 off | Creativity, memory, mood | Overstimulation, niacin flushing | No peer-reviewed studies |

| MDMA Microdose | 1–5 mg | Every 3–7 days | Empathy, connection | Neurotoxicity, serotonin crash | No controlled human data |

| Amanita muscaria | 50–200 mg muscimol extract | Daily or varied | Sleep, mood, trauma relief | Seizures, metal toxicity | Retrospective reports only |

Common Side Effects and Toxicological Risks of Microdosing

Although often described as safe due to the low doses involved, microdosing psychedelics is not free of risks. Both physiological and psychological side effects have been reported in observational studies and case series. Moreover, the use of poorly regulated or non-standardized products—especially in the case of Amanita muscaria—adds an additional layer of toxicological uncertainty. The following table summarizes the most commonly observed adverse effects and toxicological concerns reported in recent literature.

Table 4. Summary of frequently reported adverse effects and toxicological risks associated with psychedelic microdosing. Effects vary depending on the substance, dose, individual physiology, and source quality. Data compiled from systematic reviews and health warnings by regulatory agencies. References: : Modzelewski et al. (2025), Kinderlehrer (2025), Cameron et al. (2021), Microdosing Institute, ACS Lab Amanita Guide.

| Section | Description |

| 4.1 Common Side Effects | According to a 2025 systematic review, microdosing may cause: - Increased anxiety or restlessness - Sleep disturbances - Elevated heart rate or blood pressure - Gastrointestinal discomfort - Headaches or mild nausea These symptoms were typically dose-dependent and resolved within 24 hours. However, repeated effects led some participants to withdraw from studies. |

| 4.2 Toxicological Risks | Amanita muscaria products have been linked to toxic reactions, including: - Seizures - Confusion (especially from unregulated sources) In 2024, the CDC issued warnings after several hospitalizations related to commercial Amanita edibles. Long-term use of psychedelics, especially without supervision, may pose risks such as: - Tolerance development - Cardiovascular strain - Heavy metal accumulation (from natural mushrooms) - Psychological dependency or misuse |

Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classify psilocybin as a Schedule I substance. This means it's officially considered to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use—a classification it shares with substances like heroin and LSD.

However, despite this strict classification, the FDA has taken important steps that reflect a growing recognition of psilocybin’s therapeutic potential. Over the past few years, the FDA has granted “Breakthrough Therapy” designation to psilocybin-based treatments. This special status is reserved for drugs that, based on preliminary clinical evidence, show substantial improvement over existing therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

Here’s a timeline of key FDA designations:

2018 — Psilocybin was granted Breakthrough Therapy status for Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD).

2019 — It received the same designation for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

2024 — The FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation to CYB003, a next-generation psilocybin analog currently being studied as an adjunctive treatment for MDD.

These designations accelerate clinical trials and regulatory review, signaling that psilocybin may soon become an approved, evidence-based treatment for certain mental health conditions. While it remains a controlled substance for now, the FDA's evolving position highlights how the scientific and medical understanding of psychedelics is rapidly advancing.

Conclusion

Microdosing has captured the imagination of thousands around the world, offering hope for mood enhancement, mental clarity, and emotional healing. However, in 2025, the science remains inconclusive. Most controlled studies show limited or placebo-matched benefits, while safety and dosing remain variable and largely self-regulated.

There is no universal protocol, no gold-standard compound, and no one-size-fits-all answer. But there is a clear need for more rigorous research, particularly around long-term safety, standardization, and neurobiological mechanisms.

Until then, those engaging in microdosing—clinicians, researchers, or individuals—must proceed with curiosity, caution, and critical thinking.

How do I Microdose?

- The Importance of Testing: Ensuring Safety in Microdosing

Before starting any psilocybin microdosing regimen, it's essential to do your research and make some decisions. Questions to ask and answer include:

- Why do you want to microdose?

- Why have you chosen a specific substance?

- What do you hope to gain from the experience?

- Is the substance you’ve chosen legal for personal or medically supervised use in your state? If not, do you understand the potential legal ramifications?

- Have you discussed the benefits and risks of magic mushroom microdosing with a health professional?

- Do you plan to microdose on your own or under the supervision of a health professional?

If you’re considering experimenting with LSD, MDMA or psilocybin microdosing, it’s essential to approach it responsibly and choose the protocol that is optimal for you under your responsibility. One of the most critical aspects of this is ensuring that you know exactly what you’re consuming. This is where testing becomes invaluable.

QTests measurement of potency before consumption

At miraculix, we offer QTests that allow you to determine the precise concentration of LSD, MDMA and psilocybin in the substances you plan to use. These tests provide a safe and effective way to measure dosage, which is especially important for microdosing mushrooms. Unlike full doses, where the effects are immediate and noticeable, the subtle nature of psilocybin microdosing makes it easy to accidentally take more than intended if the dosage isn't properly calibrated.

Our QTests empowers you to make informed decisions by knowing de amount of what you're consuming. If you're looking to enhance your well-being through microdosing, accuracy and safety should be your top priorities.

Want to try a QTest to measure the concentration of psilocybin in your mushrooms for microdosing? Check out our webshop to get started. If you'd like to learn more about how our test works, feel free to visit the FAQ section for detailed information.

FAQ: What Is Microdosing?

This FAQ section addresses the relevant scientific, clinical, and methodological questions surrounding psychedelic microdosing. Drawing from peer-reviewed studies, pharmacological data, and harm-reduction frameworks, it aims to clarify current knowledge, common misconceptions, and ongoing areas of uncertainty within the field. Each answer is designed to support evidence-based understanding without promoting or endorsing use.

Microdosing involves taking a sub-threshold dose of a psychedelic compound—such as LSD, psilocybin, MDMA, or Amanita muscaria—to improve mood, focus, or emotional resilience without inducing hallucinations. It works by subtly modulating neurotransmitter systems, especially serotonin, though the placebo effect may also play a role.

The most commonly used substances are LSD, psilocybin (magic mushrooms), MDMA, and muscimol extracted from Amanita muscaria. Each has distinct mechanisms of action and safety profiles.

Reported benefits include improved mood, focus, creativity, emotional balance, and cognitive flexibility. However, many of these claims remain anecdotal, and scientific studies have shown mixed or placebo-matched results.

Yes. Common side effects include anxiety, insomnia, headaches, or gastrointestinal discomfort. Risks are higher with repeated use or unregulated products—especially Amanita muscaria, which has been linked to seizures and confusion. Long-term effects are not yet well understood.

Some small studies and case reports suggest possible benefits, but large, placebo-controlled trials have shown inconsistent outcomes. More rigorous research is needed to determine long-term safety, efficacy, and mechanisms of action.

Fadiman’s protocol involves dosing every third day to allow for tolerance reset and reflection, while Stamets’ stack includes daily dosing for 5 days followed by 2 days off, often combined with Lion’s Mane and niacin. Neither protocol has been tested in placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Low doses of psychedelics may modulate neuroplasticity, reduce neuroinflammation, and influence serotonin and dopamine signaling. However, most mechanistic data come from studies using full psychedelic doses; whether these effects occur at microdose levels remains under investigation.

Amanita muscaria contains muscimol, a GABA-A agonist, not a serotonergic compound. Toxic reactions—including seizures and confusion—have been reported, especially with unregulated extracts. The CDC and FDA have issued safety alerts in 2024 regarding commercial products.

Factors such as dose variation, set and setting, expectancy effects, and product inconsistency (especially in natural mushrooms) all challenge reproducibility. There's also a lack of validated outcome measures specific to microdosing.

References

- ACS Lab. (n.d.). Amanita muscaria dosage guide: Extracts & tinctures. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.acslab.com/mushrooms/amanita-muscaria-dosage-guide-extracts-tinctures

- Cameron, L. P. (2021). Asking questions of psychedelic microdosing. eLife, 10, e66920. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.66920

- Healthline. (2021). A beginner’s guide to microdosing. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.healthline.com/health/beginners-guide-to-microdosing#the-research

- Joyous Team. (n.d.). Guide on how to microdose. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.joyous.team/blog/guide-on-how-to-microdose

- Kinderlehrer, D. (2025). The effectiveness of microdosing psilocybin in neuropsychiatric Lyme disease: a case study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2025. https://www.dovepress.com/the-effectiveness-of-microdosing-psilocybin-in-neuropsychiatric-lyme--peer-reviewed-article-NDT

- Microdose.me. (n.d.). Microdose. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://microdose.me/index.html

- Microdosing Institute. (n.d.). Microdosing. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://microdosinginstitute.com

- Modzelewski, S., Stankiewicz, A., Waszkiewicz, N., & Łukasiewicz, K. (2025). Side effects of microdosing lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin: A systematic review of potential physiological and psychiatric outcomes. Neuropharmacology, 271, 110402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2025.110402

- SAGE Journals. (2023). Asking questions of psychedelic microdosing. SAGE Open Medicine, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231225609

- Turkia, M. (2024). Psycholytic dosing or ‘microdosing’ of Amanita muscaria (red fly agaric) mushrooms—A retrospective case study. Psychedelic Therapy, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451902224000156

- Zamnesia. (n.d.). Paul Stamets’ microdosing protocol: Everything you need to know. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.zamnesia.com/blog-paul-stamets-protocol-n2010

About the author

Dr. Marina Garcia Moreno – Scientific Author

Dr. Marina Garcia Moreno is the Chief Scientific Officer at miraculix Lab, where she leads scientific development focused on harm reduction, drug checking, and psychoactive substance analysis. She holds a PhD (Dr. rer. nat.) in Medical Microbiology and Bacteriology from Friedrich Schiller University Jena (Germany), and has over 8 years of experience in biomedical and translational research.

Before joining miraculix, Dr. Garcia Moreno worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the University Clinic Jena. Her academic training includes a Master’s degree in Biomedicine and Molecular Biology from the University of the Basque Country.

As a multilingual science communicator, she is deeply committed to science-based education, public health, and bridging the gap between research and society. Through her writing and development of analytical tools, she aims to make scientific knowledge accessible, reliable, and actionable for a broad audience, from professionals to the general public.

You can learn more about her background on LinkedIn.