The Science of LSD

In our scientific work, in dealing with psychedelic substances, it is important to us to also report on these and to shed more light on them.

Therefore, we would like to start our series of articles "The Science of Psychedelics" today. In this series we would like to draw attention to the social and scientific relevance of psychedelics. For this purpose, we regularly present current knowledge from research.

In this blog post, we would like to take a closer look at LSD. In the overview you will learn more about :

1. the history (What does LSD have to do with bicycles?)

2. pharmacology (how does LSD work in the human body?)

3. medicine (how can LSD help sick people?)

4. chemistry (What is LSD and where does it come from?)

What does LSD have to do with bicycles?

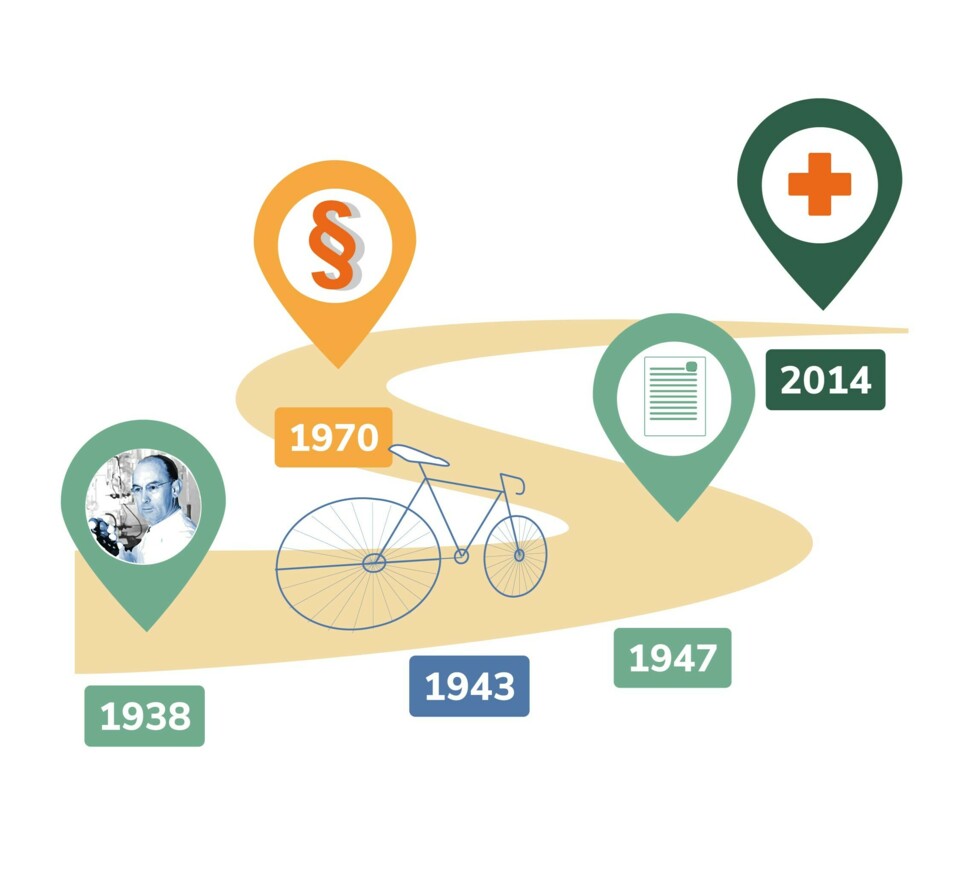

LSD was first synthesized in 1938 by Dr. Albert Hofmann in Basel, Switzerland.[1] He discovered the psychedelic effects of LSD by accident on April 16, 1943, when he accidentally came into contact with the substance while handling it.[2]

In a self-experiment, he discovered these effects 3 days later and was under the full influence of the substance on his way home by bicycle, which is why this day (April 19) is also called Bicycle Day. After the first study of medical use in 1947, there were more than 1000 publications on over 40,000 people.

Despite this, in 1970 it was placed in the most restrictive category of drugs, giving it a high potential for abuse and safety when used by a physician. More than 40 years later, a change occurred during the psychedelic renaissance, there was a change in image and, as a result, more studies for medical use on humans.

How does LSD work in the human body?

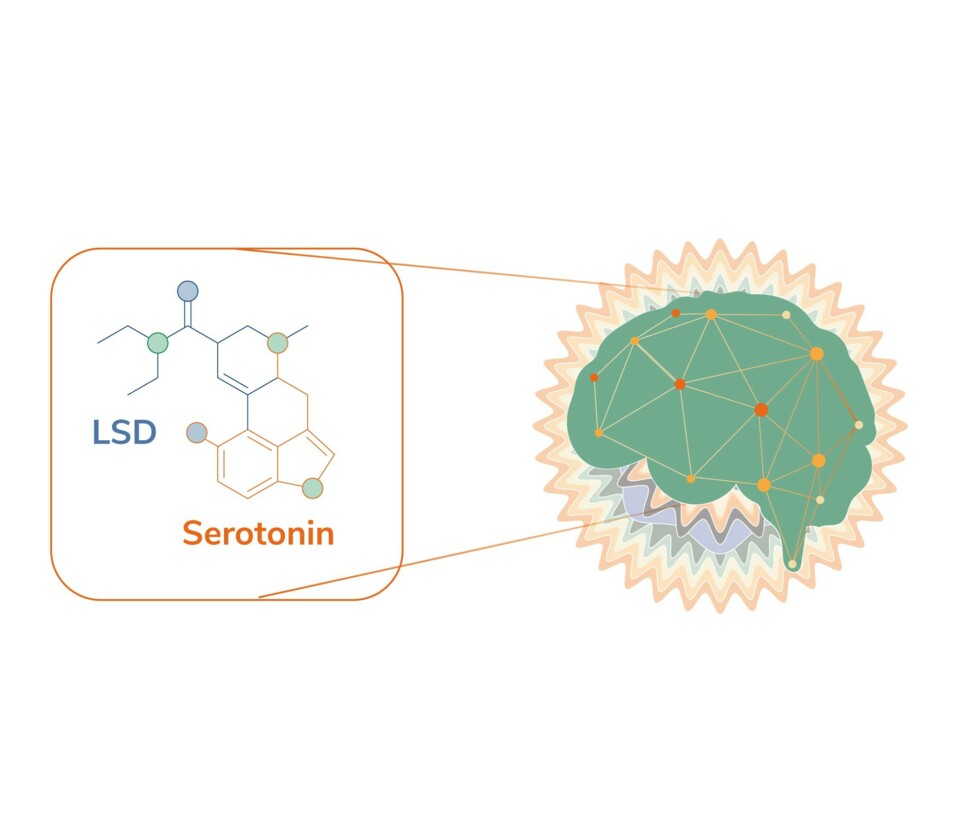

LSD is very similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin. Therefore, it interacts with the so-called 5HT2A receptors, which triggers the psychedelic effects.[3]

Similar to psilocybin, it could be shown that in the psychedelic state, areas of the brain communicate with each other that do not otherwise do so.[4]

Due to the fact that LSD fits almost perfectly into this receptor, it is already effective in the μg range (about 50 millionths of a gram), which is why it is easy for doses can occur.[5]

The research associated with LSD has led, among other things, to the discovery of the serotonergic system and has therefore been important for understanding the human brain.

How can LSD help sick people?

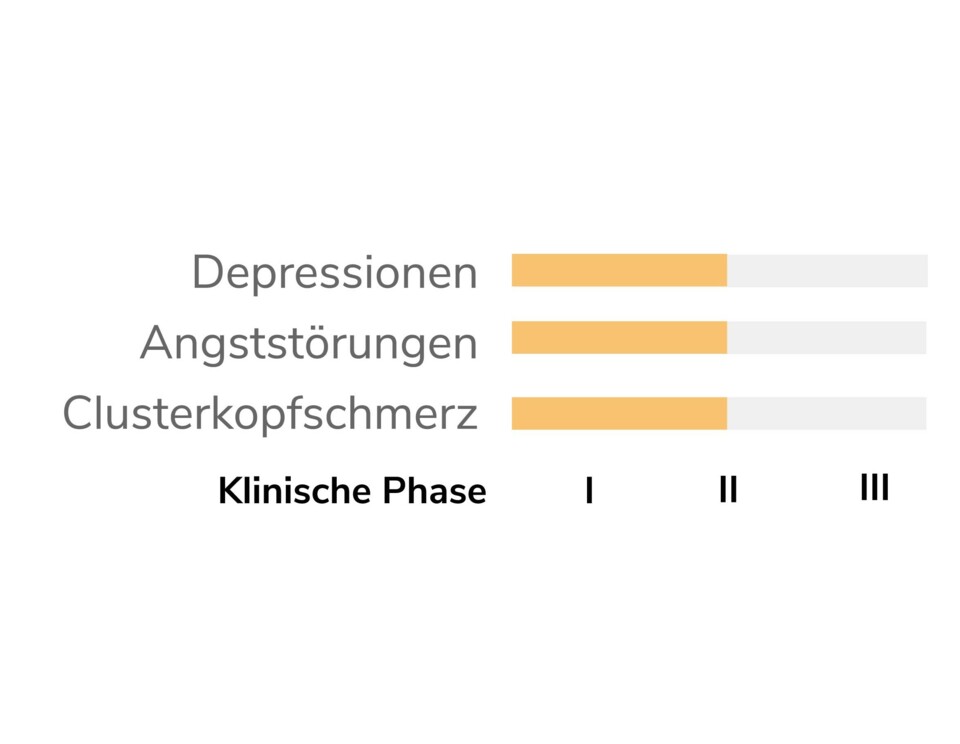

In addition to the countless completed studies, there are currently over 20 ongoing or planned studies on the medical use of LSD, mainly supported by the charity Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).[6]

It has been shown to be most effective in the context of psychotherapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders in terminally ill patients and in depression and has also been successfully investigated in phase II clinical trials.[7]

It has also been a positive effect on cluster headaches.[7]

Thus, LSD and other psychedelics offer a promising new therapeutic approach.

What is LSD and where does it come from?

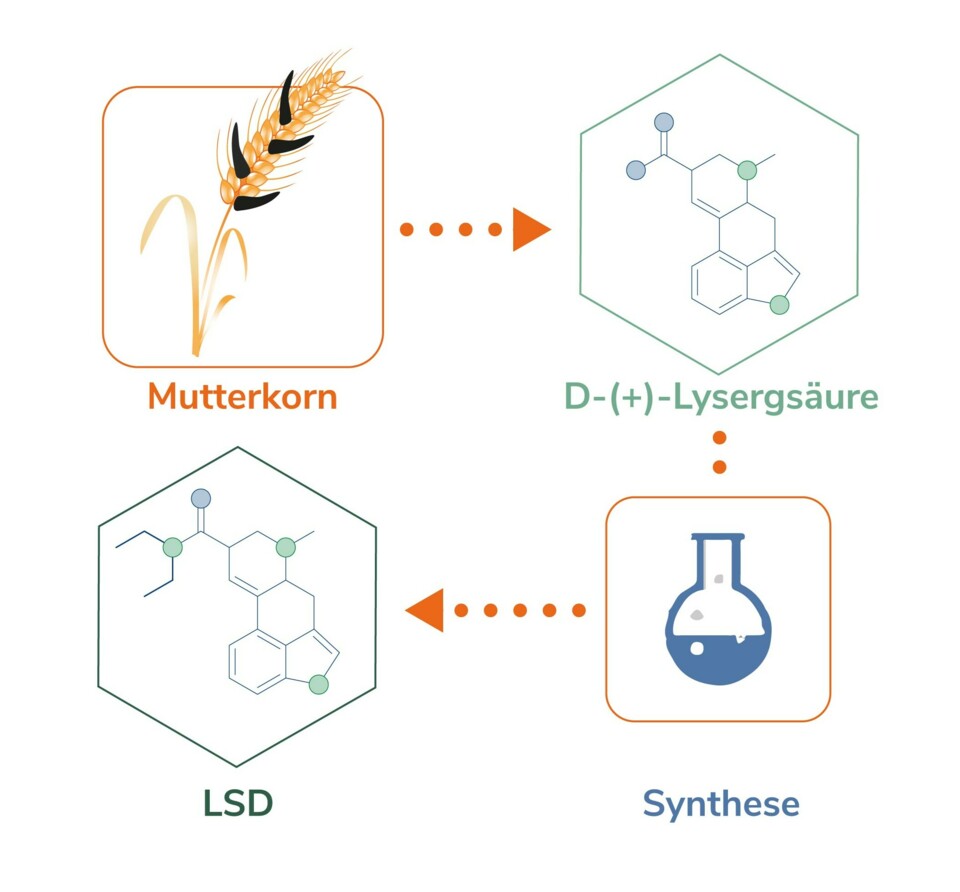

Lysergic acid diethylamide (or also LSD-25; lysergide; delyside) is a semi-synthetically produced substance from the class of the ergoline derivatives. The name "LSD-25" comes from the fact that it is the 25th substance in Hofmann's test series of synthetic lysergic acid derivatives.[1]

The precursor of LSD, D-(+)-lysergic acid, can be found in nature especially in ergot fungi, such as Claviceps purpurea, which is mainly Rye infests. Once isolated from these mushrooms, the lysergic acid in its activated form can be converted by reaction with diethylamine to produce LSD.

[1] A. Hofmann, LSD. Mein Sorgenkind, Klett-Cotta, 2015.

[2] A. Hofmann, Agents Actions 1970, 1, 148–150.

[3] D. E. Nichols, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2331–2343.

[4] E. Tagliazucchi et al., Curr. Biol. 2015, 26, 1043–1050.

[5] K. Kim et al., Cell 2020, 182, 1574-1588.e19.

[6] www.clinicaltirals.gov maps.org

[7] R. G. dos Santos, J. E. C. Hallak, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 423–434.

More Blog Articles

Related blog articles that might interest you.

The Science of 2C-B

Blog articles about 2C-B (4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxy- phenylethylamine ) and the categories history, chemistry, pharmacology, medical use and the analysis.

THE Science of Magic Mushrooms

Blog articles on magic mushrooms and the categories of biology, anthropology, medicinal uses, and pharmacology.

The Science of MDMA

Blog articles on MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) and the categories History, Pharmacology, Toxicology and the Medical Uses.